Across the aisle: The hole in the budget

The National Health Protection Scheme is entirely unfunded. If it is a jumla (akin to the announcement in Budget 2016-17), there is nothing to worry. But if the government rolls out the scheme in 2018-19 and buys insurance for the beneficiaries, it has to spend money. Estimates vary from an optimistic Rs 11,000 crore to a realistic Rs 1,00,000 crore.

When the numbers are finally put in the left or right column and a balance is struck, the government’s Budget statement does not look much different from a homemaker’s household budget. If we ignore the zeros, it could be the annual household budget of a rich family.

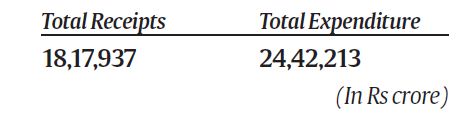

Take a look at the numbers of India’s annual Budget for 2018-19:

The deficit is Rs 6,24,276 crore. In the case of a homemaker, there is no option but to borrow the money, if he or she has the capacity to borrow and someone is willing to lend. In the case of the government, the option is the same — to borrow — but the conditions are different.

- A government will borrow, whether it has the capacity to borrow or not. Some governments borrow beyond their capacity and leave a huge debt for the succeeding government.

- A government may borrow in the hope that the borrowing will be temporary and the ‘excess’ borrowing can be set off by finding additional receipts within the year.

Behind the Numbers

According to Budget 2018-19, the Central government will borrow Rs 6,24,276 crore. This is the famous Fiscal Deficit (FD). As in the case of all numbers, the true story is not visible by just looking at the numbers. One must go behind the numbers and that is what I propose to do in this essay.

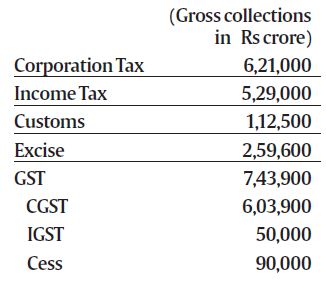

First, let’s look at the receipts. The bulk of the receipts is made up of tax revenue (net to the Central government). The major heads of taxes and what they are expected to fetch are in the following table:

The elephant in the room is the Goods and Services Tax (GST). The GST was introduced on July 1, 2017. As per data published by the Controller General of Accounts (CGA), in the period August 2017 to January 2018, CGST collections (including IGST settlement) averaged Rs 22,129 crore per month. The Budget assumes that the average collection will rise to Rs 44,314 crore in February and March 2018, and then increase to Rs 50,000 crore per month in 2018-19. This strains credulity.

On a generous assumption that CGST collections will increase to Rs 40,000 crore per month, and an annual collection of Rs 4,80,000 crore, there will be a shortfall of Rs 123,900 crore (gross) and of Rs 71,862 crore (net to the Centre at 58 per cent).

The other question mark on the Receipts side is Disinvestment Receipts. In 2017-18, the budget estimate (BE) was Rs 72,500 crore but the revised estimate (RE) is Rs 1,00,000 crore. This was achieved by a sleight of hand: asking ONGC to buy the government’s shareholding in HPCL and pocketing Rs 36,915 crore. Can it be repeated in 2018-19? If that is not possible, the BE of Disinvestment Receipts in an election year of Rs 80,000 crore (more than the BE of 2017-18) appears difficult to achieve. Hence, there could be a hole under this head too of, say, about Rs 20,000 crore.

Understated Expenditure

Let’s look at the expenditure side. There are two gaping holes.

Firstly, the provision for food subsidy. In 2016-17, it was for about Rs 1,10,000 crore, and in 2017-18 the estimate is about Rs 1,40,000 crore. The provision for 2018-19 is about Rs 1,70,000 crore. The increase of Rs 30,000 crore in 2018-19 may not be sufficient. The NDA government was quite miserly in granting minimum support prices (MSP). Considering it is the election year, the government made a grand announcement of giving MSP at ‘Cost plus 50 per cent’. It is still not clear how the ‘cost’ will be reckoned. But if the government were to announce large increases in MSP, the provision of Rs 1,70,000 crore will not be sufficient.

Secondly, the National Health Protection Scheme is entirely unfunded. If it is a jumla (akin to the announcement in Budget 2016-17), there is nothing to worry. But if the government rolls out the scheme in 2018-19 and buys insurance for the beneficiaries, it has to spend money. Estimates vary from an optimistic Rs 11,000 crore to a realistic Rs 1,00,000 crore. That number has to be added on the Expenditure side. Under these two heads, my guess is that the government will be required to spend another Rs 70,000 crore-Rs 20,000 crore for food subsidy and Rs 50,000 crore for health insurance.

How Big is the Hole?

I have not taken into account any rise in crude oil prices. The Budget seems to have assumed that crude oil price will remain below USD 70 per barrel. If that number goes up, there will be serious trouble. When we add these numbers on both sides of the statement of account, we will have a shortfall of about Rs 92,000 crore on the Receipts side and additional outgo of Rs 70,000 crore on the Expenditure side — that is an addition of Rs 1,62,000 to the fiscal deficit.

The FD In 2018-19 is, therefore, not likely to be contained at Rs 6,24,276 crore or 3.3 per cent of GDP. It may rise to Rs 7,86,276 crore or 4.15 per cent of GDP. The markets are watching. You should be too, because the borrowing is your debt.

→

→

0 comments:

Post a Comment